The affordable energy transition

It is not too good to be true, it is the economic reality that lies ahead of us.

The

energy transition facing us in the coming decades is an affordable one.

In fact, the future energy system is not only affordable, it is cheaper

than the energy system we have today. And this creates an opportunity

to invest more to achieve the future we want.

Let

me be more precise: in just one generation, humanity will be spending a

much lower share of its GDP on energy than it does today. The main

reason is not energy prices, but energy efficiency. Whether you believe

in the phenomenon of peak energy, as DNV GL does, or just increased

efficiency, the conclusion is the same, and it is robust.

Affordability

is reward enough, but there is an even more important win – we are

heading towards a decarbonized energy future. But do not pop the

champagne yet. Our Energy Transition Outlook (ref. 1) outlines the most

likely future as DNV GL sees it. The energy transition, modelled to the

best of our ability, is far too slow; we are not on track for a

Paris-compliant future.

Some of the savings that

therefore accrue from a much more efficient energy system need to be

ploughed into speeding things up, investing in R&D, technology

support, policy incentives and other activities increasing the pace of

the transition.

And even if society does invest and

achieve Paris ambitions, the transition is affordable, purely in energy

economic terms. The stakes beyond energy economics are of course far

larger; the costs of runaway global warming are close to incalculable.

What should

count as ‘energy expenditures’ is open to debate. DNV GL’s Energy

Transition Outlook uses a strict definition, including only fossil-fuel

extraction, refinement and conversion, installation and operation of

renewable energy plants, and all costs incurred by the power sector.

The

definition could have been extended with energy efficiency measures,

energy transport costs, and energy support and subsidies. Using our

definition, present expenditures are at 4.6 trn USD annually, and will

grow in absolute terms to 5.6 trn USD annually in 2050, as illustrated

in Figure 1.

There are different views of the unit costs

of energy going forward. Renewable energy production will inevitably be

cheaper, while grid complexity increases and will be more expensive.

Fossil energy extraction is helped by technology improvements, but is

also moving to more challenging conditions.

Without going

into details, it is likely that the relative costs of a unit of energy

will stay within the same range as today. On a global accumulated level,

DNV GL figures show average energy costs slowly increasing from 8 to 10

USD/GJ over the next 30 years.

But

the world economy is growing at a much faster speed than energy

expenditures. With an average expected growth in global GDP of 2.6% per

year the global economy will be 130% larger than it is today.

Illustrated in Figure 2, this is a story about affordability.

Would this conclusion change

if we included costs that are excluded from our energy expenditure

definitions? No. The costs would add to the absolute costs and

percentages, e.g. fossil fuel subsidies today are in the range of 400 bn

USD (ref. 2), renewable subsidies at 150 bn USD (ref. 2), and energy

efficiency costs at 240 bn USD (ref. 3).

The first is

likely to decrease the coming decades, the two latter to increase, but

the change in the figures will remain too small to alter the overall

conclusion.

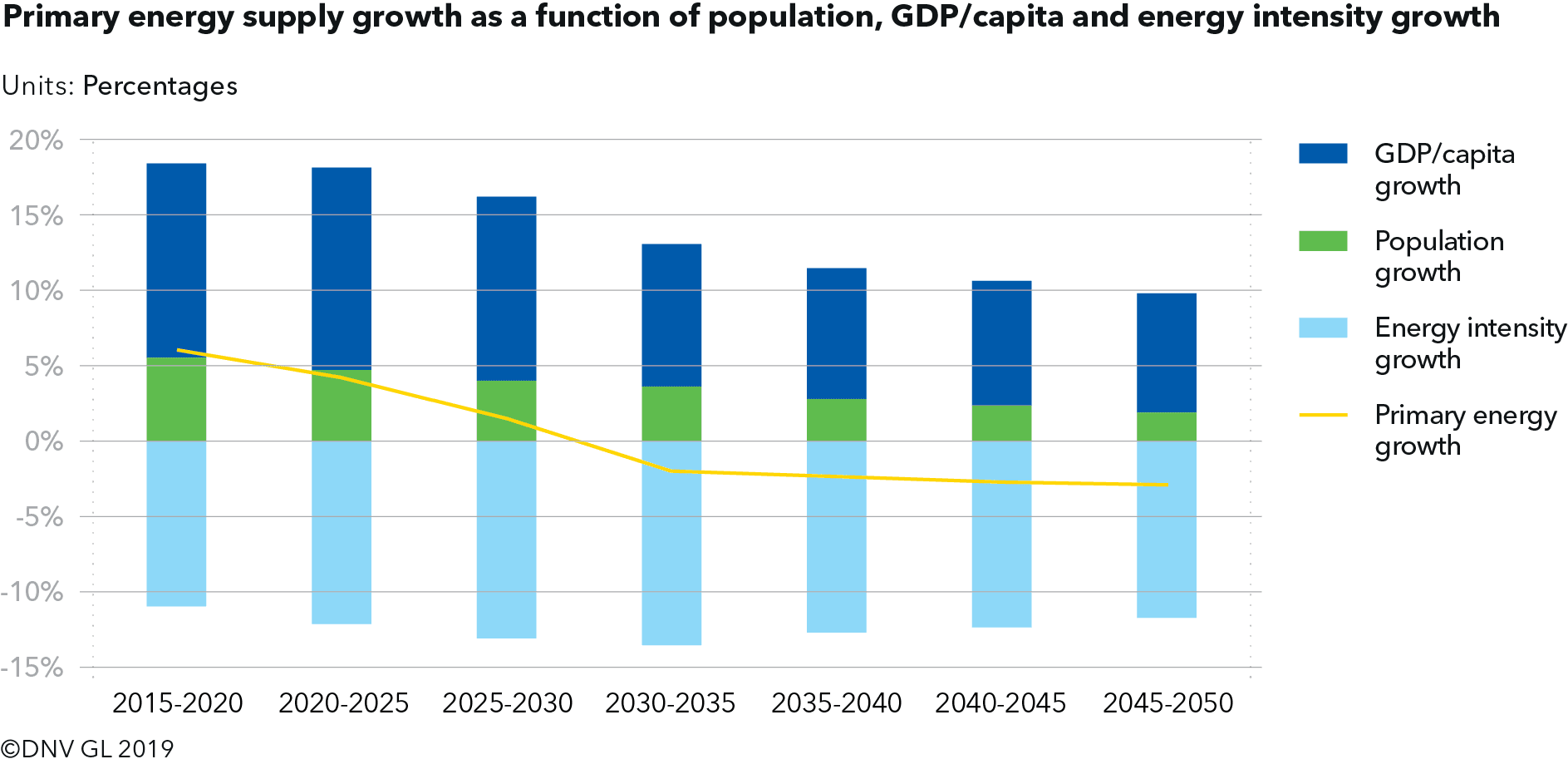

The overarching driver

of affordability is energy efficiency. This is best illustrated as

improvement in global energy intensity – the global primary energy

consumption per unit of GDP. Energy intensity has improved 1.6% per year

over the last decades.

With increased electrification

and more efficient energy end use in all sectors and all regions, we

expect global energy intensity reduction to be 2.5% per year on average

towards 2050.

The shift gives us the watershed moment of

peak energy, when humanity – in spite of population and economic growth

and great improvements in energy access for poorer populations – will

start to use less energy (ref. 4).

The main reason for

the affordable transition is the reduction – both absolute and relative

to economic growth – in global energy use, not changes in energy costs.

The

market, left to its own devices, tends to be short-sighted. Unless

forced by rules and regulations, most energy developments are

economically rational in the short term. What if we forced the energy

system to achieve Paris ambitions, would this be costly? Yes and no.

Various

references exist on the cost of achieving Paris ambitions. Most of them

also include the benefits of reducing climate change damages.

However,

if we confine ourselves narrowly just to the extra costs involved in

decarbonizing the energy system, that could add up to an additional

annual cost of 0.4-0.8% of GDP (ref. 5). If we add this number to the

GDP share for energy expenditures shown in Figure 2, we see that the

transition is still affordable, with a clear margin.

The

conclusion that the energy transition is affordable is valid even

without considering the benefits of avoiding the dangerous consequences

of global warming, which obviously are compelling.

Something for the COP 25 negotiators to bear in mind!

Sverre Alvik is the Energy Transition programme director, DNV GL-

UNSW student-designed solar freezer installed on remote Fiji islandby Sophie Vorrath on 28 November 2019 at 10:46 AM

-

Winners and losers from Victoria’s rooftop solar rebate schemeby Nigel Morris on 28 November 2019 at 9:47 AM

-

Solar and battery microgrid achieves 90% renewables for W.A. gas hubby Sophie Vorrath on 26 November 2019 at 3:03 PM

-

The Driven Podcast: Why your EV will also be a “virtual power plant”by Giles Parkinson on 29 November 2019 at 2:41 PM

-

Audi technical update adds 25km to e-tron all-electric SUVby Bridie Schmidt on 29 November 2019 at 2:27 PM

-

Tesla Model S busts EV myths with historic 1 million kilometres drivenby Bridie Schmidt on 29 November 2019 at 1:53 PM

:quality(85)/https%3A%2F%2Freneweconomy.com.au%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F05%2FArarat-Wind-Farm-Australia-14-3000px-copy-3-300x255.jpg)

:quality(85)/https%3A%2F%2Freneweconomy.com.au%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F11%2Fcybertruck-electric-ute-300x169.jpg)

:quality(85)/https%3A%2F%2Freneweconomy.com.au%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F11%2FClimate-Council-State-of-Play-score-card-300x163.jpg)

:quality(85)/https%3A%2F%2Freneweconomy.com.au%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F10%2F3-1000-x-450-300x135.jpg)

:quality(85)/https%3A%2F%2Freneweconomy.com.au%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F09%2FScreen-Shot-2019-09-25-at-12.46.16-pm-300x197.png)

:quality(85)/https%3A%2F%2Freneweconomy.com.au%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F11%2FLendlease-sydney-buildings-carbon-neutral-Barrangaroo-Waterfront-2-optimised-300x169.jpg)

powered by plista

powered by plista

No comments:

Post a Comment