Christianity Today Exposed the Reality of Evangelical Division

Here’s why a single editorial ignited an online firestorm.

| 14 min |

| 2 |

This week, Christianity Today, a deeply respected Christian magazine (the analogy is imprecise, but think of it like an Evangelical version of National Review, but focused on theology and church life) ignited a days-long firestorm when it published an editorial declaring, “Trump Should Be Removed From Office.”

The piece directly referred to the magazine’s stand against Bill

Clinton in 1998, and then ended with these direct and unsparing words:

This week, Christianity Today, a deeply respected Christian magazine (the analogy is imprecise, but think of it like an Evangelical version of National Review, but focused on theology and church life) ignited a days-long firestorm when it published an editorial declaring, “Trump Should Be Removed From Office.”

The piece directly referred to the magazine’s stand against Bill

Clinton in 1998, and then ended with these direct and unsparing words:We have reserved judgment on Mr. Trump for years now. Some have criticized us for our reserve. But when it comes to condemning the behavior of another, patient charity must come first. So we have done our best to give evangelical Trump supporters their due, to try to understand their point of view, to see the prudential nature of so many political decisions they have made regarding Mr. Trump. To use an old cliché, it’s time to call a spade a spade, to say that no matter how many hands we win in this political poker game, we are playing with a stacked deck of gross immorality and ethical incompetence. And just when we think it’s time to push all our chips to the center of the table, that’s when the whole game will come crashing down. It will crash down on the reputation of evangelical religion and on the world’s understanding of the gospel. And it will come crashing down on a nation of men and women whose welfare is also our concern.The president has responded, falsely calling it a “far left magazine” (it’s theologically orthodox and relatively centrist). Pro-Trump Christian leaders have responded. Christianity Today’s web servers were strained by the traffic. Think pieces are flooding Christian media, and all-out Twitter brawl is under way.

But why? Hasn’t all this been litigated before? Didn’t the failure of the “Against Trump” issue of National Review show that magazines should stop telling people how to think? Hasn’t the Evangelical rank-and-file moved on from hand-wringing about Trump, and aren’t they all aboard the Trump train? And, if so, why did virtually all of Trump’s big Evangelical defenders train their fire on Christianity Today? That’s the conventional wisdom, at least.

In fact, however, the alleged Evangelical monolith is more conflicted than outside observers understand, and Donald Trump’s unique presidency is placing more strain on theologically serious Evangelicals than most Americans perceive.

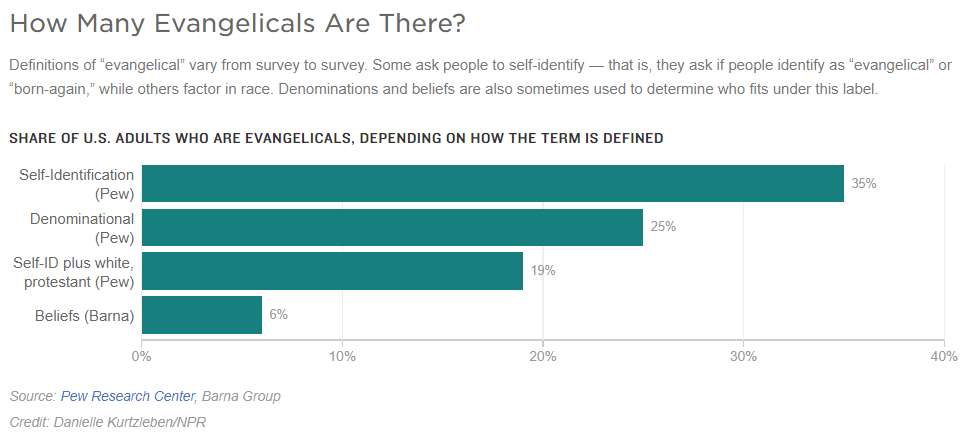

I added theology as a qualifier because not all self-described “Evangelicals” share the same beliefs or the same faith habits. Exit poll questions about religious identity are far too imprecise to provide true insight into a complex community. Many people who describe themselves as “Evangelical” simply because it’s the best option in a limited exit-poll menu don’t go to church often and don’t subscribe to all the key tenets of Evangelical belief. When they hear “Evangelical” they often interpret it as “politically conservative Christian.” To understand the malleability of the definition, look at this chart, from an NPR story collecting data on different definitions of Evangelicalism:

Christianity Today

is not a magazine for the 35 percent. It’s a magazine for the 6

percent, and its editorial is article aimed like an arrow at that

audience. Many of the 35 percent not only don’t share the same

theological beliefs as that smaller cohort, they’re completely

indifferent to Evangelical documents like the Southern Baptist

Convention’s 1998 Resolution on Moral Character of Public Officials.

If you ask them if they believe (to quote the resolution) that

“tolerance of serious wrong by leaders sears the conscience of the

culture, spawns unrestrained immorality and lawlessness in the society,

and surely results in God’s judgment.” They’ll have a one-word answer:

“Nope.”

Christianity Today

is not a magazine for the 35 percent. It’s a magazine for the 6

percent, and its editorial is article aimed like an arrow at that

audience. Many of the 35 percent not only don’t share the same

theological beliefs as that smaller cohort, they’re completely

indifferent to Evangelical documents like the Southern Baptist

Convention’s 1998 Resolution on Moral Character of Public Officials.

If you ask them if they believe (to quote the resolution) that

“tolerance of serious wrong by leaders sears the conscience of the

culture, spawns unrestrained immorality and lawlessness in the society,

and surely results in God’s judgment.” They’ll have a one-word answer:

“Nope.”But the 6 percent is different—and Trump’s more savvy Evangelical defenders know it. Christianity Today’s audience represents their colleagues and peers. The 6 percent represents the Americans who tend to affirm all nine conventional theological criteria of Evangelical orthodoxy:

They say they have made “a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in their life today,” that their faith is very important in their life today; believe that when they die they will go to Heaven because they have confessed their sins and accepted Jesus Christ as their Savior; strongly believe they have a personal responsibility to share their religious beliefs about Christ with non-Christians; firmly believe that Satan exists; strongly believe that eternal salvation is possible only through grace, not works; strong agree that Jesus Christ lived a sinless life on earth; strong assert that the Bible is accurate in all the principles it teaches; and describing God as the all-knowing, all-powerful, perfect deity who created the universe and still rules it today.These Americans—who possess a very high view of God’s sovereignty and are disproportionately engaged in the ministry of the church—look at the language from the Southern Baptist resolution, take a deep breath, and worry. In fact, they worry about a lot of things. They worry about abortion, about religious liberty, about racial reconciliation, and the church’s public witness. Also, the 6 percent isn’t all “white Evangelical.” It’s multi-ethnic, and when the views of non-white Evangelicals are taken into account, the gap between Trump and Clinton narrows significantly.

Moreover, the Trump administration is putting this 6 percent in a continual, relentless, and escalating bind. It would be one thing if Christians held their nose in 2016, voted for a man with a checkered past, and then he not only delivered on judges but also behaved like a decent human being in office. Trump has delivered on judges, to be sure, but he has behaved abominably (it’s not just “mean tweets”; I don’t take seriously anyone who boils his misconduct down to mere “rudeness” or “bad tweets”) even as he also demands extraordinary and effusive public loyalty from his allies.

In normal circumstances, Christians could clearly and consistently call out Trump’s misdeeds while they applaud his good decisions. But those who consistently seek his ear often feel like they cannot do that. They must circle the wagons around Trump. So at best, they’ll remain silent when he does plainly terrible things. At worst, they’ll become like those who the Prophet Isaiah condemned: “Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness.”

The pressure is substantial. To make Trump’s election “worth it,” it’s necessary to secure policy victories. To keep securing policy victories, one may stay close to Trump. Staying close to Trump all too often forces Christians to defend the indefensible.

While Christians can in good conscience vote for Republicans or Democrats (or for a third party), it’s simply wrong to condemn actions in the other party that you rationalize from your own president (or worse, to condemn actions from others even as you excuse or ignore more egregious conduct from your own side). It’s wrong to conveniently adjust your theology to meet the political needs of the moment. Yet that’s what many members of the 6 percent have done. They’ve compromised to a point that would be unrecognizable and offensive to the person they were even as recently as 2015, and many of those individuals are deeply uncomfortable with their decision.

Trump’s most zealous Christian defenders feel no such conflict. But they know something that most readers of the New York Times don’t. They know that the heart of the church is torn, and that many of the faithful—especially those middle-aged and younger—who show up to worship services every week, who perform the lion’s share of the ministry and work of the church, and who are most likely to interact with non-Christians at work and in school, see the cost of the Trump alliance, and despair.

In that context, each public Christian voice who declares he or she is not afraid to face a future without Trump—and that there is a spiritual aspect to political choices that can’t be measured in statute books or judicial nominations—encourages other Christians who share the same concerns. Ever-so-slightly, it shifts the terms of the debate. It decreases the perceived isolation of the Trump-skeptical Evangelical, and it reinforces the idea that one can oppose Trump while not compromising one inch on underlying theological and cultural commitments to life, religious liberty, and the family.

As I read the Christianity Today essay, I was reminded once again of the words of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: “You can resolve to live your life with integrity. Let your credo be this: Let the lie come into the world, let it even triumph. But not through me.” Donald Trump is bringing an avalanche of lies into this world. It’s time for Christians once again to consider whether they want those lies to come through them—through their votes and their voices.

A preview of coming attractions ...

Before Christianity Today blew up the internet, I was intending to take this newsletter in a very different direction—how Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling’s online plight illustrated why Christians are right to be concerned about the future of public discourse. It’s still an important story, and I’ll explore it later this week. Stay tuned.

One last thing ...

I got a fantastic reader response to the song I attached at the end of my last newsletter. So, here’s my church’s worship band again. They’re called “We the Kingdom” if you want to find them on iTunes/Spotify/etc. It’s a very different song from last week. Enjoy!

Photograph of Donald Trump by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

| 2 |

No comments:

Post a Comment