October 4, 2019

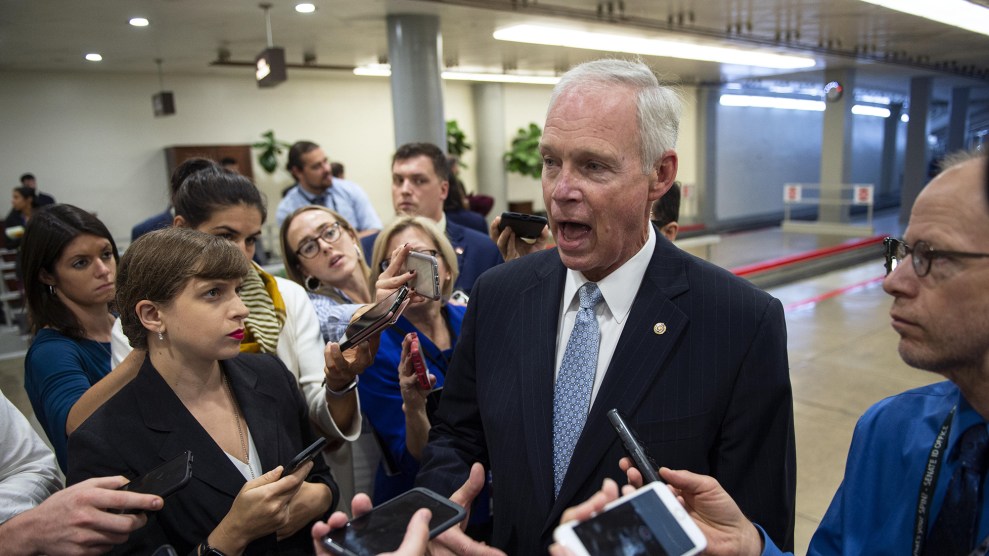

This Ancient Fruit Holds Secrets for How to Farm in Climate Change

Respect your elder-berries.

Heiko Wolfraum/dpa/AP

Cloverleaf Farm,

a small produce operation in Davis, California, managed to do okay

during the extreme drought that lasted from 2012 to 2016. But in the

first wet year after the long dry period, the farm lost its entire

apricot crop to disease—$40,000 to $50,000 down the drain.

Researchers predict that as climate

change worsens, there will be more frequent shifts between extreme dry

spells and floods. As Cloverleaf learned the hard way, the phenomenon is

already taking a toll on growers in the country’s largest food

producing state. During the drought, California’s agricultural and

related industries lost $2.7 billion in one year alone. Big cash crops like almonds and grapes are at particular risk in the future, unnerving farmers and vintners already taking hits from erratic and extreme weather.

Katie Fyhrie, a grower at Cloverleaf Farm, worries that

the farm won’t be able to keep producing stone fruits—which depend on

the timing and duration of winter chill—in the long-term. “It

can be confusing to figure out how to move forward,” Fyhrie says.

“Where we’re at right now, versus where we’re going to be 10, 20, 30

years down the line. It’s a really tricky thing to balance.”

Learn more about how climate change is transforming dinner—and how farmers are fighting back—on the latest episode of Bite:

Ancient plant species might hold important clues about which crops will survive in a harsher climate. With that in mind, Fyhrie and her team have started growing elderberries. An

indigo pearl-sized fruit that grows on a big bushy plant, the

elderberry is relatively unknown in the United States; the majority of

the commercial market comes from an imported European variety. But

Native American communities have been using a Western elderberry

subspecies for centuries.

The elderberry that’s native to

California grows remarkably well in drought conditions. After a couple

of years, you can completely remove irrigation and the plant will keep

producing. This last season, Cloverleaf harvested 130 pounds of berries

from each of its most mature trees, none of which are irrigated. “That

is a huge deal that we’re getting berries that are good for you, really

versatile for a lot of products, and that require no additional

fertilizer or water,” Fyhrie says.

Sign up for our newsletters

Subscribe and we'll send Mother Jones straight to your inbox.

Elderberries are just one of “many hardy

ancient foods and crops that may be a poised to make a twenty-first

century comeback,” as Amanda Little puts it in her recent book The Fate of Food: What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World.

Global warming is “forcing us to think differently about the quality

and resilience of the crops we grow—both in the poorest parts of the

world and the wealthiest,” she writes. Some researchers

are trying to breed almonds, apples, and avocados that are more

resistant to hot weather and drier saltier land.

General Mills is now using Kernza—derived

from ancient perennial wheatgrass native to the Kansas plains—in some

of its cereals, snack bars, and crackers. In comparison to traditional

wheat, Kernza is much more sustainable and better at sequestering

carbon.

With support from a sustainability grant

from the California Department of Food and Agriculture awarded in fall

of 2018 and in partnership with the University of California–Davis,

Cloverleaf is running field trials with elderberries, developing best

practices guides for growers, and doing nutritional and market analyses.

The idea is to explore boosting grower adoption and consumer interest

in the berry.

At Cloverleaf, Fyhrie uses the fruit in

syrup, jelly, and even fruit leathers and an elderflower cordial. Dried

elderberries can be used for tea and baked goods. They’re also used in

food coloring and dyes. Because of the berries’ antioxidant and antiviral

properties (in certain subspecies at least), they’re popular in the

health food community and are commonly used as supplements or to treat

colds and flu.

Elderberries won’t replace apricots any time soon.

Developing ancient and native crops or breeding new ones comes with a

host of complications and long lead times. Processing elderberries

requires a lot of labor, and they can be hard to digest. Kernza grains

are less than a quarter the size of standard wheat grains, making

harvesting difficult and costly, as Little points out, and recent crop

failures limited General Mills’ Kernza rollout. Plus, changing consumers’ tastes is no easy feat.

But, there’s potential. When I stopped by the Davis Food

Co-op on my way home from Cloverleaf, the woman at the wellness counter

told me elderberries haven’t reached CBD status, but she’s definitely

noticed an uptick in products lining the shelves. At first, Kernza was

only used in boutique west coast breweries and bakeries; now it’s being

adopted by one the country’s largest multinational corporations. So to Fyhrie, exploring new options like elderberries feels worth the squeeze.

She thinks it’s important to start to

“really think about what type of plants can we get away with not

watering, can we get away with putting less fertilizer, can deal with

the heat, don’t need as much chill in the winter,” she says. “The more

that we start to incorporate those now—while we have the water to

establish them—the more resilient small farms will be in the future.”

We Recommend

Latest

We have a new comment system!

We are now using Coral, from Vox Media, for comments on all new articles.

We'd love your feedback.

view comments

No comments:

Post a Comment